|

|

|

Introduction

The vast Melton Road works at Leicester was without doubt the most important of the British lamp factories. During its six decades of existence, virtually every kind of light source was manufactured in its giant production halls. There is perhaps no other factory in the world which could boast having produced the entire gamut of incandescent, halogen, fluorescent, low and high pressure sodium, mercury, quartz and ceramic metal halide, neon, xenon, electrodeless, automotive, projection, infra-red, ultra-violet and even LED lamps. In parallel the adjacent Research & Engineering laboratories made countless contributions of global significance to the development of new lamps, and a good deal of the modern types still in production elsewhere continue to rely on groundbreaking developments in materials, science, engineering and manufacturing technologies which were established at Leicester. Sadly its long trail of success came to an end in 2007 when, after a prolonged period of under-investment, it was finally closed in favour of lower cost overseas labour.

|

The HQ Building and Research Labs, showing approx. half of the Lamp Works behind, circa 1980

The HQ Building and Research Labs, showing approx. half of the Lamp Works behind, circa 1980

|

| Address |

Melton Road, Leicester, LE4 7PD, United Kingdom |

| Location |

52.668°N , -1.105°E |

| Opened |

1940 (with start of lampmaking in 1946) |

| Closed |

2007 |

| Products |

Incandescent GLS, Incandescent Miniature, Incandescent Projection, Incandescent Infra-Red, Incandescent Automotive, Halogen Automotive, Halogen Mirrors MR11/MR16, Halogen Cookers, Halogen Photo/Projection/Studio, Sealed Beam, Linear Fluorescent, Sodium SO/SOX/SLI/SON, Mercury MA/MB/MBF, Metal Halide MBI/MBIL/Arcstream/Ceramic, Short Arc Metal Halide, Short Arc Xenon, Linear Neon, Electrodeless Discharge, LED Die & Packages, Special Products, Stellox ceramics, dichroic coatings, tungsten coiling, lampmaking machinery.

|

Early History

The main factory building was constructed in 1939/40 by Associated Electrical Industries, a company then largely owned by General Electric of America. It was initially operated by one of AEI’s subsidiaries, the British Thomson-Houston Company, to manufacture aircraft magnetos and starter-motors for the war effort. BTH had decided to establish Leicester as a shadow factory for the nearby Coventry works to ensure continued supply of these critical parts in case Coventry should be bombed.

Leicester survived the war, but naturally the market for its products declined quickly. Meanwhile the demand for both lamps and electronic valves was booming, and BTH could no longer cope with the volume of orders at its existing operations in the nearby town of Rugby. Additional floor space was required for the installation of new manufacturing equipment, particularly for the recently introduced fluorescent tubes which had been developed at the beginning of the war. Rather than further extend the cramped facilities at Rugby which had since been dwarfed by BTH’s activities on that site for the manufacture of heavy electrical goods such as steam turbines, generators and diesel-electric locomotives, it was decided to relocate lamps and valves to some of the company's other sites.

In 1946 the first light source production groups arrived in Leicester. These were for the manufacturing of fluorescent and automotive lamps, followed swiftly by mercury and sodium discharge lamps. Following the success of the transfer, in the coming years all of BTH’s lampmaking operations were decentralised from the Rugby Headquarters, to allow that site to concentrate on heavy electrical engineering. Incandescent lamps for general lighting were transferred to the new Mazda works in Trent Vale, and the remaining special incandescent / projection lamps moved to the Ediswan works at Ponders End, London, which BTH had owned since 1928. For a short period special valves such as Ignitrons and Hydrogen Thyratrons were also made at Leicester, but when BTH's activities in these products were transferred to English Electric, the valve production moved again to EE's Lincoln factory.

The reliance of the Leicester lamps on advanced new technologies in materials and manufacturing techniques brought with them a requirement for a concentrated research effort in order to maintain the company’s leading position. As a result, much of the Lamp Research group at the Rugby HQ also migrated to Leicester, with the result that it soon became one of the world’s key sites for the development and manufacture of advanced new light sources. During the following decades a significant proportion of the world’s innovations in electric lamps came from Leicester and the factory continued to grow in parallel.

In addition to lamps and lamp technologies, the Leicester site also housed a subsidiary company known as 'Manifold Machinery Ltd.', later renamed MSU, the Manufacturing Systems Unit of Thorn Lighting. This was engaged entirely in the design and construction of tooling and machinery for the production of electric lamps, and had a satellite operation at the Enfield lampworks. The equipment factory had impressive capabilities for building the largest high speed fully automated machines, for instance lathes capable of turning metal parts of more than a metre in diameter, as well as implementing the latest technologies in production process controls.

|

Transition from AEI to Thorn Lighting

Almost since the foundation of BTH and its successor AEI by General Electric of America, GE had favoured an amalgamation of the entire British electrical industry to create a single giant organisation, on the scale that it enjoyed in America, which would dominate the British Empire and keep smaller competitors at bay. GE's influential president Gerard Swope made repeated attempts to persuade the heads of British GEC, English Electric, British Siemens and Ediswan to either amalgamate with AEI's subsidiaries BTH and Metropolitan-Vickers, or sell out to GE. During this period it was kept secret that GE in fact already owned the controlling interest in AEI, and there can be no doubt that GE's real ambitions were to establish its own full control over the British electrical companies. So long as each of those companies however had its own lampmaking operations, where the real money was being earned in the electrical industry, they were able to subsidise the slower and often loss-making heavy electrical sides of their businesses and retain their independence.

Swope therefore began covertly buying large quantities of shares in his competitors via third parties, at one point coming critically close to acquiring controlling interest in the unrelated General Electric Company of England. Its chairman, Hugo Hirst, was acutely suspicous and swiftly moved to deny all foreign shareholders of the right to vote on the company board. This successfully stopped Swope in his tracks, but during the 1950s it was becoming increasingly obvious that indeed there were merits to his plans, and even the UK Government gave its support to such a scheme (by then, GE's covert controlling shareholding in AEI had been eliminated under the antitrust laws).

The emphasis was primarily on the heavy electrical side where mounting financial losses were plaguing British enterprises. Smaller goods such as lamps and domestic electrical appliances were by contrast immensely profitable, and required no such protection. Perhaps in preparation for a possible amalgamation of the heavy electrical businesses, AEI Lamp & Lighting Co. was established as a separate entity from the parent AEI Group in 1956, and its company headquarters was set up beside the lampworks at Leicester. At that time a large new building was constructed, visible in the foreground of the photograph above, with the front wing to house the company board and senior management, and the remainder being devoted to the Lamp Engineering Department. A generous Pilot Plant area was also provided behind these buildings, for the construction of new production equipment which could initially be operated under close supervision of the lamp engineers, before relocation across the road into the Lampworks.

The coming years indeed saw a change in ownership, and during 1958-59, an 11% stake in AEI Lamp & Lighting was sold jointly to its key competitors : 5.5% to each of Thorn Electrical Industries and Osram-GEC. A fierce battle ensued between these two companies, each desiring to increase its shareholding and fully take over the AEI Lighting operations and the jewel in its crown, the Leicester site, to give that company control of one of the world’s most advanced lighting research and manufacturing operations and the subsequent growth that it would guarantee.

Meanwhile, AEI was plagued by mounting financial losses in its heavy electrical business, which were partly due to its failure to successfully integrate its subsidiary companies BTH and Metropolitan-Vickers - both of whom had an essentially similar product range but operated their own independent factories and sales organisations. It was becoming standard practice for one AEI subsidiary to undercut the other's offer in order to win the business, often repeatedly, until there was practically no remaining opportunity for the ultimate victor to earn any profit. Similarly each company endeavoured to build larger and more spectacular factories than the other, which ultimately proved to be little more than showpieces as they were invariably never filled to the capacity they were designed for. In 1960 the chairman, Lord Chandos, resolved to end the company's longstanding internal conflicts via the immediate abolition of all of the old brand names, to be replaced by the single new name of AEI. Although AEI had existed since 1928 to manage the merged BTH, Metrovick and later Ediswan companies, it was only a holding company and as such its name was completely unknown. The disappearance of the old brands created even more bad feelings and proved to be disastrous for AEI because even customers didn't know who this company was, and it lost a significant market share in the early 1960s.

While the General Electric Company of England (no connection with GE of America) was in negotiation with AEI over the merger of their entire businesses, Jules Thorn, founder and chairman of the small and independent Thorn Electrical Industries, showed no interest in the heavy electrical operations and kept a sharp focus on the more profitable smaller products. In 1959 he persuaded AEI to form a joint venture with Thorn to manage its 'Hotpoint' domestic appliances business, and again in 1961 merged its Electronic Valve and Cathode Ray Tube production with that of Thorn, remarkably allowing Thorn to take control of the new company.

In 1964 GEC and AEI signed an agreement of their intentions to merge. The rate of subsequent progress in the negotiations was however slow, and in its thoroughly weakened state, AEI's need for cash was rapidly mounting becasue the risk was becoming real that it might simply be taken over by GEC. At the end of 1964 while discussions were taking place between GEC and AEI, a lifeline was offered by Jules Thorn who had a burning desire to achieve nothing more than increase his 5.5% stake in AEI's subsidiary, AEI Lamp & Lighting Company. His success in lamps, valves, television and domestic appliances had allowed him to increase his capital such that he could afford to buy a 65% stake in AEI L&L - and without a moment's hesitation his offer was snatched from under GEC's nose. It was a move that was ultimately to create intense bad feeling at GEC, who had of course wanted to see the profitable lamps business included in a potential merger with AEI. To make matters worse, Thorn had further negotiated an option to increase his shareholding to 100% if he could raise the cash to do so within the following three years.

And so it was, that on 31st December 1964 the control of the AEI Lamp & Lighting operations was transferred to British Ligthting Industries, a fighting company that Thorn had set up a few months earlier with the specific intention of merging his operations with those of AEI. AEI retained a 35% shareholding in BLI, and of course Thorn's arch-rival, Osram-GEC, still held onto its 5.5% share that it had acquired previously. BLI at this time gained control of the Leicester site along with ten other British lamp factories, as well as AEI's stake in certain Australian, New Zealand and South African lampmakers, and its interests in the component producers Lamp Metals Ltd, Lamp Caps Ltd, Glass Bulbs Ltd, and Glass Tubes & Components Ltd. These had formerly been joint AEI-GEC factories which controlled the British production of the lamp components used by themselves and practically all other British manufacturers, as well as a substantial part of the overseas demand. It was the job of the transitionary company, British Lighting Industries Ltd, to restructure, rationalise and integrate all of the new operations with those of Thorn, and several of the former AEI lamp factories were closed in the following years. The new company BLI went from strength to strength under the leadership of Sir Jules Thorn, who by 1966 was able to buy 100% control of another lampmaker, Ekco-Ensign of Preston, in which he had acquired a 51% shareholding in 1949.

In the mean time the remainder of AEI plummeted further into failure, declaring disastrous financial results in 1966. The newly formed Industrial Reorganisation Committee which had been set up by the Labour Government to revitalise stagnating British industry favoured a merger of AEI with GEC and English Electric, and in 1967 proposed a £15M IRC loan to facilitate such a merger. All parties refused - GEC meanwhile, had been performing with relative success, and was clearly on the lookout for a full takeover of AEI. AEI rapidly needed cash to save itself, and in 1967 sold its prestigous Grosvenor House headquaters overlooking Buckingham Palace, which generated a desperately needed £4 million. Further help came once again from Sir Jules Thorn, who executed his right to buy out AEI's remaining 35% share in BLI within a 3-year period. On 20th October 1967, for the value of £12.3 million, he must have felt immense satisfaction in gaining 100% control of BLI. Having started just 30 years earlier as a tiny independent lampmaker which operated outside the giant worldwide lamp cartel that controlled AEI and its subsidiary lampmakers BTH, Ediswan, Metrovick and Siemens since their inception, he suddenly gained full and independent control of the number one British lighting company.

It took a further five years to fully consolidate the AEI and Thorn operations, because up to that point each company had acquired several other smaller lampmakers, but had not successfully amalgamated their operations. During this period the number of BLI lamp factories in UK was reduced from 11 to 8, and completion of the task was announced in 1972 when Sir Jules renamed his lighting division as Thorn Lighting Ltd. At that moment each of the subsidiary brand names used by the absorbed companies came to a close, being replaced by Thorn. This included the brand names Atlas, Mazda, Ecko, Ensign, Ediswan, Cosmos, Metrovick, Siemens, Omega, Nura, Britannia, English Electric and Vesta (cheap Thorn lamps made exclusively for retail in F.W. Woolworth shops at sixpence each). As it would later turn out, like Lord Chandos' experiences with AEI, this was not the most sensible move. The Thorn brand was unknown in lighting and many customers stuck to names they knew well. After a decade of waning sales particularly in the retail channel, Thorn resurrected the Mazda brand, a move which at the time saved the company from the verge of bankruptcy and gave a clear lesson in the power of a brand name.

Incidentally the sale of the AEI headquarters and cash injection from Thorn proved insufficient to secure the future of that company. On the very same day that Sir Jules had acquired the lamp & lighting operations, GEC's Arnold Weinstock proposed a complete solution to AEI's problems via his historic £120 million bid for the entire company. It was promptly rejected by the AEI board. Ten days later, Weinstock raised his bid to £152M and AEI again rejected. On 8th November came a third bid at £160M. By then it was clear that AEI was in the final throes of its death, and over half of the board accepted Weinstock's offer. GEC subsequently examined the AEI books and declared that rather than its claimed £3.7M profit for 1967, it had in fact concealed a £4.5M loss. The writing had clearly been on the wall of the AEI board room for many years beforehand.

A year later in 1968 Lord Nelson, chairman of the third electrical giant, English Electric, signed a deal which transferred its control into GEC's hands. Some four decades after GE's plans for the amalgamation of the entire British electrical industry to create one single, vast, British electrical giant, that had now taken place - albeit no longer in the hands of GE itself. However of crucial importance to this final amalgamation was that the highly profitable Lamps business was missing from the ultimate structure. GEC had lost out to Thorn on the AEI lighting operations, and even when taking over English Electric, lost out on that company's lamp factory which had in 1927 been spun off to the British company Siemens Brothers (which had gained independence from the German parent company when it was confiscated at the start of the first world war). Siemens Electric Lamps & Supplies was itself in 1954 taken over by AEI, and also came under the control of Thorn at the time of his takeover of AEI's Lamp & Lighting interests.

This left GEC's own lighting division, Osram-GEC, although still number two in the British lighting market, as a significantly smaller player and one which had been weakened by two decades of mismanagement and lack of investment in the period between the death of its founding chairman Sir Hugo Hirst in 1943, and the takeover by the young and dynamic Sir Arnold Weinstock in 1963. Even Weinstock's interests were clearly focussed on GEC's business units outside lighting, and perhaps even at this time it was in his mind that the ailing Osram-GEC lighting division had been damaged beyond repair, and he already foresaw the opportunity that would come to him 20 years later to sell Osram-GEC back to its original oweners, Osram GmbH of Germany, from whom the British operations had been confiscated during the First World War.

|

Transition from Thorn to GE Lighting

Leicester continued to experience tremendous growth during the beginning of the Thorn era, and at frequent intervals gave the market drastically improved new lamps. At its peak of operations in the early 1980s nearly 3000 staff were employed in lampmaking, with several hundred being devoted solely to lamp research and engineering.

In the years following Sir Jules Thorn’s death in 1980, the importance of his personal involvement in the company’s success became apparent. He had built a management team comprising a large proportion of technical men, many of whom had cut their teeth at the front line of lamp or luminaire design and manufacturing, as well as others having a sharp knowledge of lighting design and applications. After his death and particularly following the merger with EMI Records to create Thorn Electrical & Musical Industries, the senior management positions were progressively filled by staff having financial and commercial backgrounds, frequently with no prior involvement in the lighting industry. The lack of direction and investment from the top had a profound effect on the company’s fortunes and within a decade the once phenomenal profit margins were giving way to a struggling company on the verge of bankrupty. The Lamps group in particular suffered strongly, being a business which has always relied on advanced new technologies. There was increased competition from continental and American firms who enjoyed global markets and made major invesments in lamp research, which could not be matched by Thorn's sales revenues that were built largely on its sales from the UK market alone. Despite being the clear market leader in UK, Thorn's position globally was much less significant. The reduced flow of innovations transformed Thorn into a company better known for its commodity products, whereas the high-tech new lamps which earned considerably greater margins were increasingly being specified from its foreign competitors.

The management of Thorn EMI eventually realised that its Light Sources operation was too small to compete alone in the newly globalised markets, and decided to exit the business. It came very close to being purchased by GTE Sylvania of America, with whom Thorn had enjoyed a close technical and patent interchange agreement since 1948 for the design and development of lamps and manufacturing equipment. However GTE itself then decided to put its subsidiary Sylvania up for sale, so as to fund the transition of its core telephones business from land-based to mobile systems, and any possible takeover of another lampmaker was then off the agenda.

Meanwhile GE of America, the original founder of the Leicester site via its controlling interest in AEI and BTH, had become a company with its focus almost entirely on the American market since the international antitrust and cartel laws established after WW2 had stripped it of its controlling interests in all of the major European and Asian lampmakers. It was also in need of once again building a global presence, and had been in negotiations to re-acquire its control of Tungsram of Hungary, the dominant force in lighting for Eastern Europe. Tungsram however had no significant presence in either the UK or the former colonies where Thorn was strong, and GE’s management was quick to recognise the strength of adding Thorn to its portfolio. The Leicester and Enfield sites in particular still employed a strong arsenal of light source engineers, and thanks to Thorn's long-standing technical links with Sylvania on machine design, the company had some of the fastest and most efficient manufacturing equipment in Europe for the production of commodity light sources. Thorn also owned jointly with Sylvania a strategically important factory in Italy having state of the art production facilities for incandescent lamps, as well as other jointly owned lamp factories in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa – all territories where neither GE nor Tungsram had an interesting market share. It was felt that under the correct management of GE, whose ambitions were clearly still focussed on excellence in lamp research and manufacturing, Thorn could be put back on track and resume its once profitable position.

A deal was swiftly reached, which led to the formation of the transitionary company GE-Thorn Lamps Ltd in February 1990, under which GE took over the light source interests of Thorn Lighting. The luminaires and control gear divisions remained with Thorn. The lamp factories at Leicester and Enfield were transferred to GE-Thorn, while those at Merthyr Tydfil, Kent Street, Preston and Rodney remained under the ownership of Thorn but managed by GE-Thorn with the intention that they would be closed at the earliest convenience. By July 1992 the integration process had been completed, and GE-Thorn was transformed into GE Lighting Ltd. In a remarkable turn of events, GE was thus regaining control of a factory that had been set up almost 50 years earlier by its wholly owned subsidiary, BTH!

|

Operations under GE Lighting

Under GE’s control the future of the Leicester site was secured, but significant rationalisation took place. Much of the work being done in the R&D laboratories was duplication of efforts elsewhere in GE and could be cancelled, and of course there was some overlap in production between former Thorn and Tungsram factories. Some departments at Leicester ceased operation in favour of more efficient Hungarian or American production, whereas others were expanded to become centres of international excellence.

At this time the low voltage and infrared halogen operations at Enfield were relocated to join the Leicester studio halogen production, such that Enfield could concentrate on fluorescent activities. Meanwhile it was also decided that Leicester should take over the incandescent production that was worth saving from the other Thorn factories. Firsly, two very high speed GLS lines were transferred from Merthyr, followed soon after by the fastest candle, ball and T-bulb groups from Preston. The remaining production of those factories was abandoned or transferred to Hungary. Shortly afterwards it was decided to close Rodney, and three slow-speed lines making single coil long life lamps were transferred to Leicester. The GLS department at Leicester only remained for a few years and was not a great success. Leicester was a factory specialised in high technology lamps and believed that it could easily take in its stride the humble incandescent, the oldest of all lamp types. However to compete on a global scale in incandescent manufacturing, cost pressures are immense. The already swift twin-head Sylvania machinery from Merthyr, which could achieve 5000 lamps per hour, was not fast enough. Higher speeds were necessary to justify the cost of continued production in Britain. Leicester succeeded in increasing production speeds well above 6000 lamps per hour, the fastest at the time anywhere outside USA, but faster production always brings with it the pain of increased scrap. It proved impossible to achieve a speed-scrap compromise which could compete with the lower labour costs in Hungary and Italy, and incandescent production was stopped in 1996.

The gap left by GLS was swiftly filled with the decision to make Leicester the global centre of excellence in manufacture of Photo-Optic lamps, a category where the factory excelled on an international level in both quality and costs. GE announced the transfer of its Quartz halogen and Incandescent Projection operations from Mattoon, USA to Leicester, and the factory prospered greatly under this initiative.

Perhaps the single most important investment under GE, however, was the decision that Leicester should manufacture GE’s entire global requirements for the new generation of Ceramic Metal Halide arc tubes. Following the commercialisation of that technology by Philips in late 1994, all other lampmakers around the world needed to catch up quickly. Leicester had in fact created the world’s first CMH lamp in the Thorn days, but this was one of the many research projects that was scrapped following the takeover by GE who at the time saw limited potential for the concept. However following the Philips launch of this technology, it needed a quick solution, and since the most knowledge was located in UK, the CMH group was established at Leicester. By 1996 GE became the second company to launch a family of CMH lamps, with manufacturing at several factories in the UK, Hungary, USA and Canada, but with all arc tubes being produced centrally at Leicester. The subsequent investments in arc tube and ceramic manufacturing were tremendous and the factory benefitted strongly.

The situation continued until the mid 2000s, however in parallel to the CMH growth was a decay of the business of other products made at Leicester. The high volume departments of Halogen MR16 dichroic lamps were facing severe price erosion and competition from China, and the automotive and miniature departments were losing volume to LED solutions. These sections funded a large proportion of the overhead costs of the vast factory site, and their decline had a profound effect on the economic viability of Leicester. In parallel, the low pressure sodium SOX lamp, the only product made exclusively at Leicester and which could not realistically be transferred elsewhere in view of the age and complexity of the manufacturing equipment, was also approaching the end of its commercial lifetime. The final sign was clear when in 2005 GE closed the on-site laboratories, which for the past six decades had ensured that the factory was kept full of new products. From that point on there were no new developments and it was clear that the factory would suffer so long as it was restricted to manufacturing commodity items whose selling prices would only further decline. In November 2006 the inevitable announcement of closure was made. CMH arctubing and Studio halogen production were transferred to Hungary and most of the rest of the production was abandoned.

The factory finally closed at the end of 2007 with the loss of the last 324 jobs, just over 60 years after its opening. Some time was needed to transfer out manufacturing equipment to other GE factories, and considerable work was also required to decontaminate certain areas from chemicals used in lampmaking. By March 2009 the site had been vacated, and it lay derelict until its demolition in May 2011. A supermarket of J. Sainsbury was subsequently built on the site and as a tribute to the decades of excellence and partial replacement for the years of colourful Christmas lighting displays, a giant lamp-shaped sculpture is planned to be erected to preserve the history of this once great industrial site of true global significance. |

Site Layout

Plant Layout c.2000

|

Photographs - Mercury Lamp Section 19469

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MA Mercury Roundabout Exhaust m/c |

|

MA Mercury Roundabout Exhaust m/c |

|

MB Mercury Development Laboratory |

|

Stan Marvin, Bob Weston, Bill Quine |

|

Photographs - SOX Lamp Section 199910

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

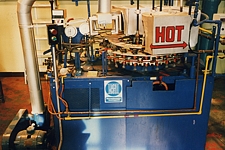

| SOX U-Bender Machine |

|

SOX U-Bender Heating |

|

SOX U-Bender Bending |

|

SOX U-Bender Annealing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SOX Tubulator Machine |

|

SOX Tubulator Machine |

|

SOX Tubulator Piercing |

|

SOX Tubulator Puddling |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SOX Tubulator Annealing |

|

SOX Pinch Machine Loading |

|

SOX Pinch Machine Sealing |

|

SOX Pinch Annealing Conveyor |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SOX Pinch Leak Testing |

|

SOX C480 Exhaust Machine |

|

SOX C480 Exhaust - Bombarding |

|

SOX C480 Exhaust - Vacuum Pumps |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SOX C480 Exhaust - Sodium Flush |

|

SOX C480 Exhaust - Tipoff |

|

SOX C480 Exhaust - Tesla Coil Test |

|

SOX Outer Bulb End Masking |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SOX Outer Bulb IR Coating Machine |

|

SOX Outer Bulb Indium Spray |

|

|

|

|

|

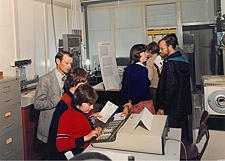

Photographs - Open Evening 1977

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.jpg) |

|

| Auto Stop & Tail Capping |

|

Miniature Butt-Seal Mount Machine |

|

Automotive Wedge Base PinchEx m/c |

|

High Pressure Sodium |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mercury Mounting |

|

SON Outer Jacketing |

|

SON Capping |

|

SLI/H Arc Tube Lathe |

|

|

|

|

.jpg) |

|

|

|

|

|

| SLI/H Mounting in Outer |

|

Discharge Circuits Lab |

|

Discharge Physics Lab |

|

Lighting Applications Lab |

|

Photographs - Open Day 1997 - The Historic Lamp Collection

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Pre-Electric Lighting |

|

Early Swan & Edison Lamps |

|

Incandescent Lamp Developments |

|

Decorative Lamps |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Discharge Lamp Developments |

|

The Largest & Smallest of Leicester |

|

|

|

|

|

Photographs - Christmas Lights

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1964 ©Leicester Mercury |

|

1998 |

|

1998 |

|

1998 |

|

Photographs - Carbon Lamp Production, 1998

In 1998 a special request arrived at GE Lighting, to view the Ediswan Collection of Historic Lamps stored at the Leicester factory with a view to identifying the kind of lamps which would have been used to light London's Savoy Theatre in the mid-1880s. That location is of special importance because in 1881, it became the world's first public building to be lit entirely by electric light. The request came from the famous director Mike Leigh, who was at the time creating a new film, Topsy Turvy, a musical drama concerning the period leading up to the premiere of Gilbert & Sullivan's "The Mikado" at the Savoy. Leigh's fastidious attention to detail is renowned and he insisted on replicating as accurately as possible the kind of lighting that would have been used at the time. Although the lamps used for the original lighting were Sir Joseph Swan's Long-Neck design, by the period in which Leigh's film was set, these had been replaced by the improved Short-Neck design of Swan's engineer, Charles Gimingham. These bear many visual resemblances to modern carbon filament lamps aside from the type of cap, and of course the presence of an evacuation tip on the bulb crown. After the visit to Leicester, Leigh was determined that the set of his film must be lighted by real carbon filament lamps to create the same warm glow of light as would have been present for the early G&S operas, and that the conspicuous pip-top must be present on the bulb. The few remaining producers of carbon filament lamps were consulted, but none were willing or able to supply Leigh with a lamp having an authentic looking pip. The request therefore came back to GE Lighting as to whether or not the company would be willing to make a thousand carbon lamps with an imitation pip for supply to the film studios. Such a small quantity would ordinarily not attract the slightest interest from such a vast organisation - but it fell on receptive ears at the company's Leicester Lampworks, who considered that it might just be possible to build such lamps by drawing on the skill of the company's glassblowers to add the glass tip, and the flexibility of the old slow-speed lampmaking machinery in the Apprentice Training Department. In parallel, the company's Public Relations staff recognised that there could be interesting publicity to gain from this event, especially since 1998 marked the 120th Anniversary of GE Lighting, and of Swan and Edison's simultaneous invention of the first practical incandescent lamps. During the summer of 1998 the lamp was designed by the author of this website who was himself then employed in the Lamp Technology Labs at Leicester, and it was swiftly put into production by that year's cohort of apprentices using the machinery of the Lamp Training Department. The carbon filaments themselves were not made at Leicester but came from old stock acquired from the former Osram-GEC Wembley factory, these having been made many years earlier by the Austrian manufacturer of carbon filaments, Elisabeth Sames and the old French supplier, F.J. & J. Planchon. American style narrow-neck A19C3 bulbs were used to better replicate the shape of the Swan originals, and the glass tips were hand-formed by skilled glassblowers from the SOX lamp production section. The photographs below show some of the stages of assembly, which were published during the celebration of GE's 120 Years of Light.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lamp Works Training Area |

|

BTH-Mazda 24-head T7 Stem Machine |

|

Stem Making on the T7 |

|

Tray of Finished Stems |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Wire Dressing |

|

Tray of Dressed Stems |

|

Bundle of Carbon Filaments |

|

Single Carbon Filament |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Filament Mounting by Apprentices |

|

Filament Mounting with Carbon Paste |

|

Pipped Glass Bulbs |

|

12-head Drop-Sealing Machine |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bulb Sealing |

|

Bulb Sealing - Fusion & Cutoff |

|

Tray of Sealed Lamps |

|

BTH-Mazda 24-head Exhaust Machine |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lamp Exhausting |

|

Lightup During Exhaust |

|

Tesla Coiling to check Vacuum Quality |

|

48-head Capping Machine |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cap Pasteing & Loading |

|

Capping Cement Curing |

|

High Voltage Blueing (Gettering) |

|

Ageing Rack |

|

|

|

|

|

|  |

|

| Finished Lamp |

|

James Hooker & CEO Mike Zafirovski |

|

Application in the Film |

|

Examples of Leicester Lamps

Incandescent

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Low Voltage Reflector |

|

A1/24 Projection |

|

Masthead Signal 3000W |

|

Airway Beacon 1200W |

|

|

|

|

Tungsten Halogen

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| T/15 Theatre Halogen |

|

CP/32 Studio Halogen |

|

Q1000T20BP Lighthouse |

|

CP/60 Sealed Beam |

|

TAL423 Display MR16 |

|

Infrared Ruby Jacketed |

Light Emitting Diode

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| GaAsP TO-18 Red |

|

GaAsP TO-18 Yellow |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Low Pressure Sodium

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SO/H Soft Glass 60W |

|

SO/H Hard Glass 60W |

|

SO/H Hard Glass 85W |

|

SO/H Hard Glass 140W |

|

SOX 135W 2nd Gen. |

|

SOX 35W 2nd Gen. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SOX 35W 3rd Gen. |

|

SOX-Plus 35W 4th Gen. |

|

SOX-E 26W 4th Gen. |

|

SOX Prototype 6W |

|

SL/H Linear Dimmable |

|

SLI/H Linear 60W |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SLI/H Linear 60W |

|

SLI/H Linear 140W |

|

SLI/H Linear 200W |

|

SLI/H Linear 200W HO |

|

|

|

|

High Pressure Sodium

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Early SON-T 250W |

|

First SON-T 70W |

|

SON-T Clear 50W |

|

SON-T 70W Cermet |

|

SON-T 400W Cermet |

|

SON-T 1000W |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SON-E Clear 70W |

|

SON-E Pearl 40W |

|

SON-E Pearl 50W |

|

SON-E KolorSON 400W |

|

SON-DLT 400W |

|

SON-DL Dichroic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SON-XLT 70W Cermet |

|

SON-XLT 400W |

|

SON-R Reflector 70W |

|

SON-TD Linear 250W |

|

SON-TD Linear 400W |

|

SON-TD Linear 1000W |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SON Sapphire Arc Tube |

|

SON Sapphire Arc Tube |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Low Pressure Mercury

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| M2 UV Glow Lamp |

|

Bayonet Cap 5' 80W |

|

MCFA Instant-Start Fluo |

|

Electrodeless Fluo 23W |

|

|

|

|

High Pressure Mercury

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MA/U Hard Glass 250W |

|

MA/H Hard Glass 1000W |

|

MAT/V Blended 500W |

|

MB/U Quartz 250W |

|

MBT/V Blended 160W |

|

MBF/U Half Coated 125W |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MBTF/V Blended 250W |

|

MBFR/U Reflector 400W |

|

MBM Coal Mine 40W |

|

MB/D Projection 80W |

|

MBL/D Laboratory 125W |

|

MB/U Photoprint 5000W |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MBW/U Blacklight 125W |

|

MD/H Water Cooled 1kW |

|

ME/D Glass 250W |

|

ME/D Prefocus 250W |

|

ME/D Box-Type 250W |

|

ME/D Oval-Type 250W |

Metal Halide

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MBI/BD 400WW |

|

MBIF/H-S 250W |

|

MBI-T 250W |

|

MBI-L Linear 1500W |

|

MBI-T 200W Prototype |

|

TSH Ceramic 150W |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| TSH Sapphire 150W |

|

CMH Ceramic 70W |

|

CID Short Arc 200W |

|

CSI Short Arc 1000W |

|

CID Short Arc 2500W |

|

Graph-X UV Printing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Calmat SBL4 400/2000W |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gas Discharge

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Linear Neon 160W |

|

Xenon Short Arc 150W |

|

Xenon Short Arc 2000W |

|

Xenon Flashlamp FA-5 |

|

Xenon Flashlamp FA-12 |

|

Xenon Flashlamp FA-7 |

| 1 |

Private Communication, Oliver Hooker, former BTH Leicester engineer. |

| 2 |

A Visit to AEI Leicester Factory, AEI Engineering Journal, Sept/Oct 1962, pp.242-247. |

| 3 |

Local Industries : Thorn Lighting, The Leicester Graphic, Vol.38 No.299, November 1980, pp.60-66. |

| 4 |

Brightly Shine the Bulbs at Night, The Leicester Chronicle, February 9th 1979, pp.10-11. |

| 5 |

Anatomy of a Merger : A History of GEC, AEI and English Electric, R.Jones & O.Marriott, Pan Books Ltd, 1970. |

| 6 |

Various issues of Thorn Lamplighter, internal factory magazine. |

| 7 |

Various issues of GE Enlighter, internal factory magazine. |

| 8 |

Thorn Lighting Manufacturing Systems Unit Company Profile. |

| 9 |

BTH History, Thurmaston Heritage Group. |

| 10 |

GE Lighting Leicester, Lamp Training Dept, The SOX Lamp, 1999. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|